SUSIE

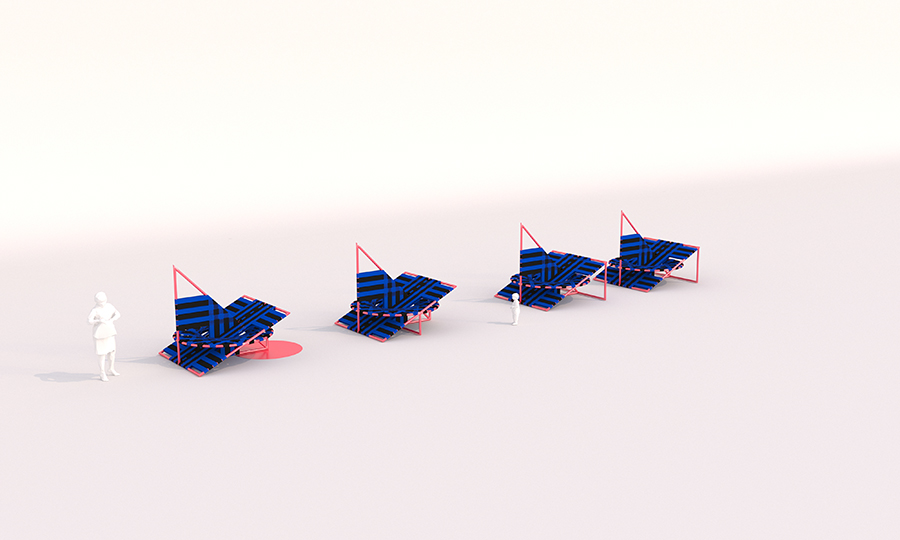

REST AND RELAXATION FOR MPAVILION

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA, 2022

Recognizing a deep need for recuperation in today’s pressurized society, Susie is an installation that engages concepts of fitness, rehabilitation, and recreation. A shortening of “suspended activation,” Susie explores how the capacity to rest might be architecturaly trained as a strategy of resistance. Susie was designed and produced for MPavilion in Melbourne and was first shown within the public program “Location, Staycation, Vacation” in January 2022, curated by Naomi Milgrom Foundation’s Creative Director, Jen Zielinska.

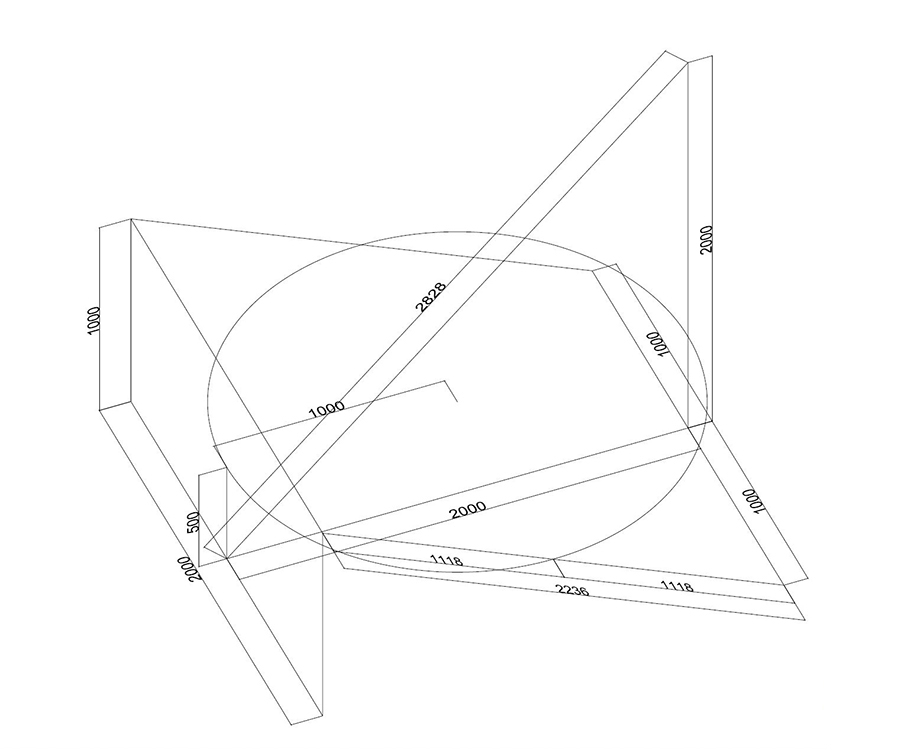

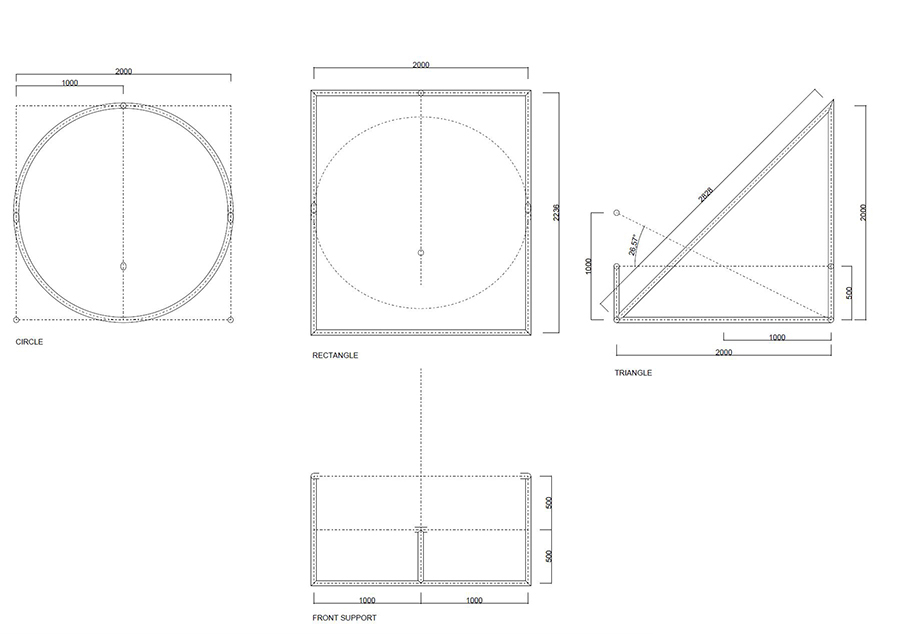

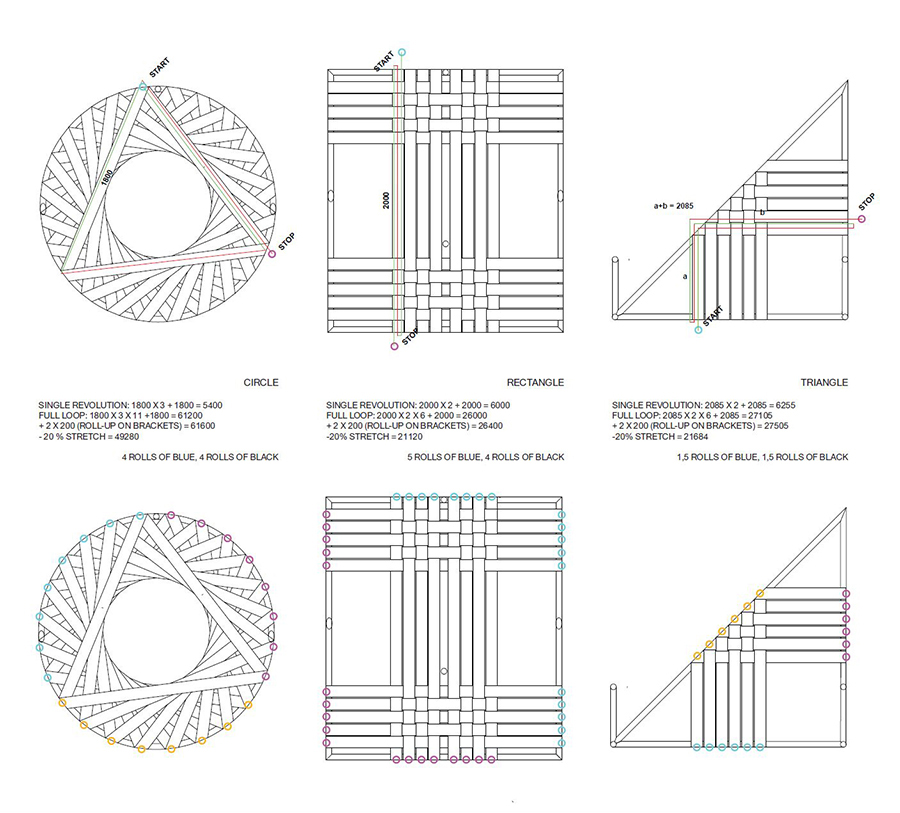

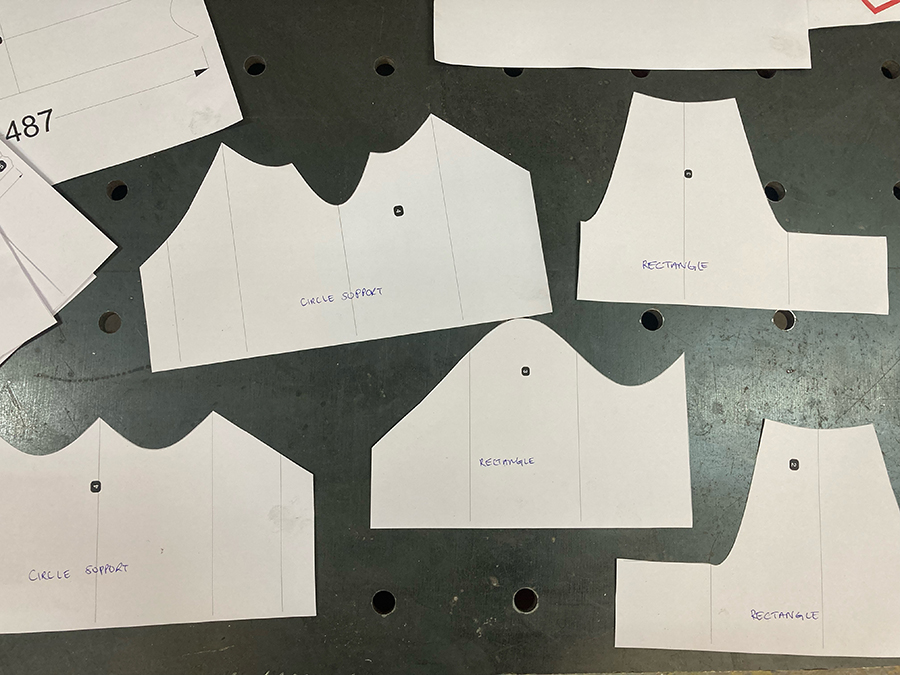

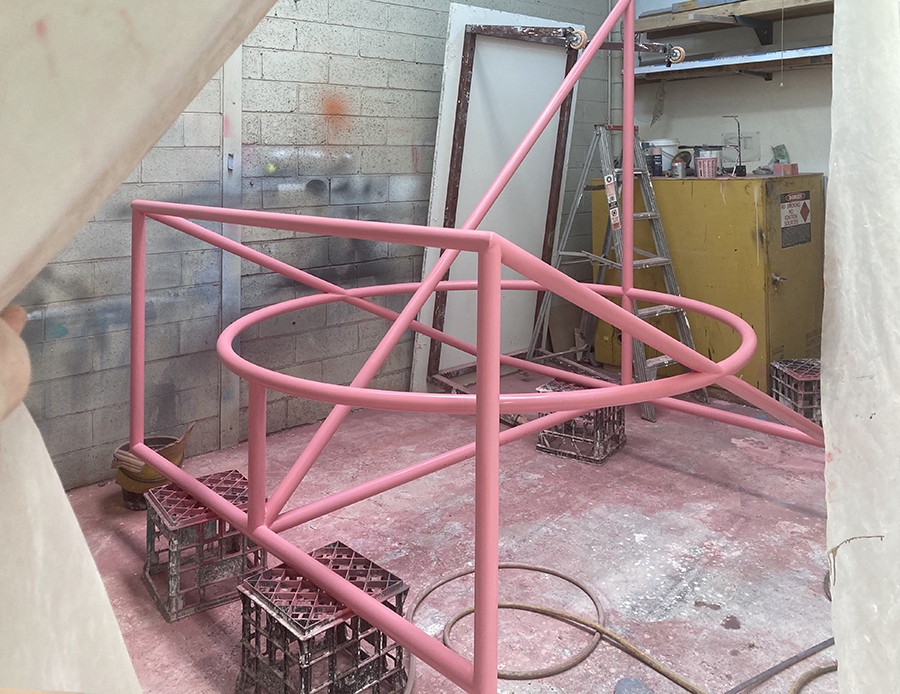

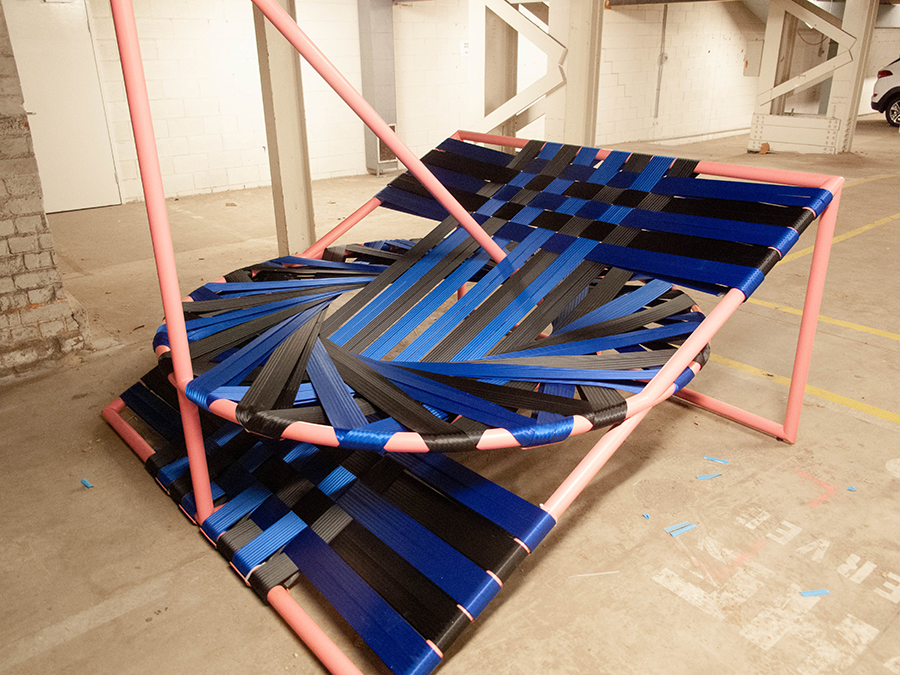

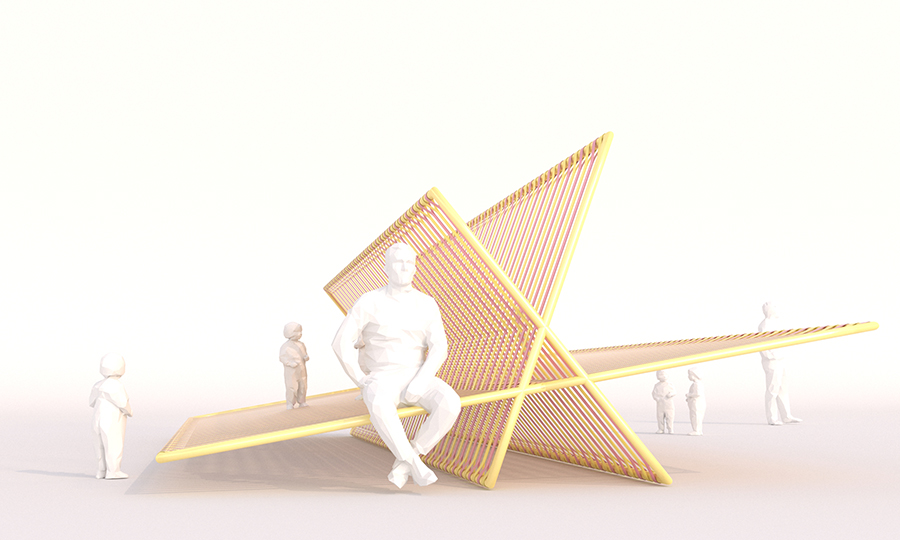

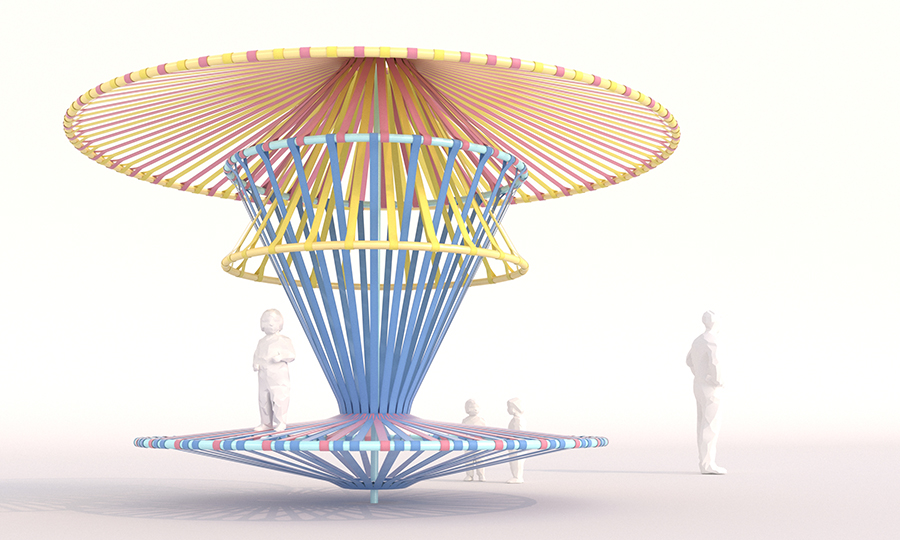

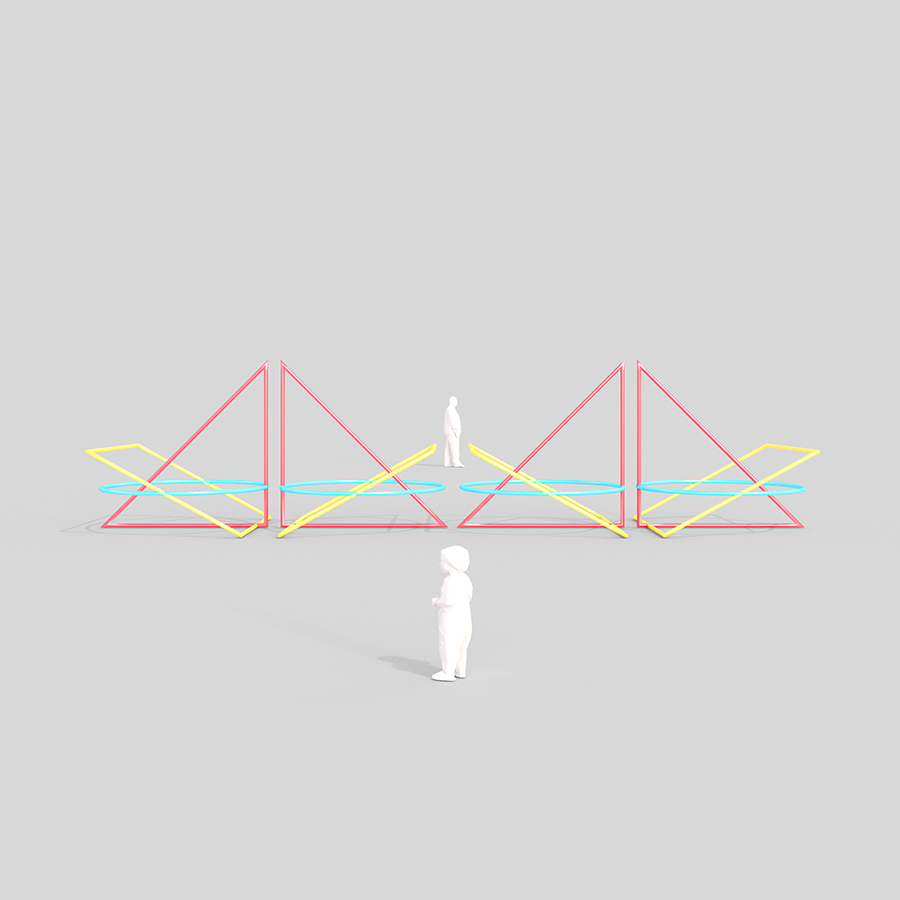

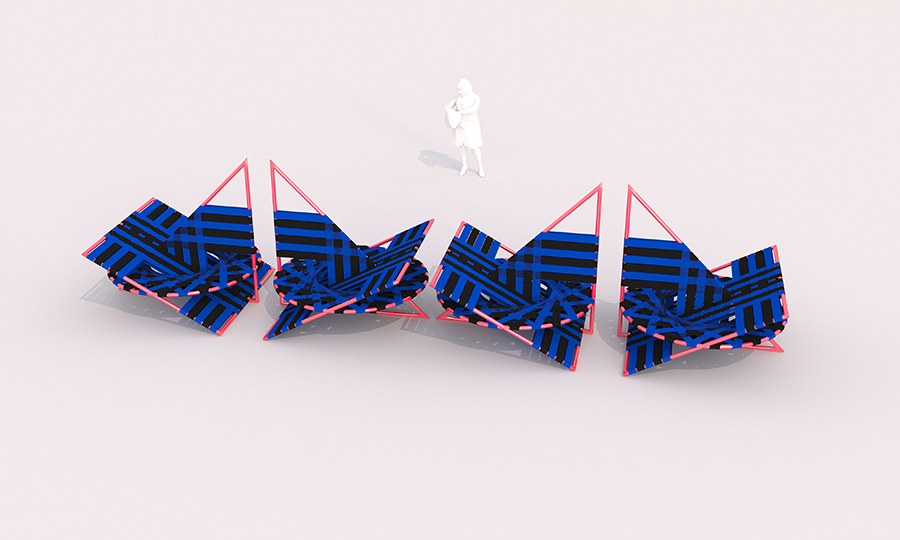

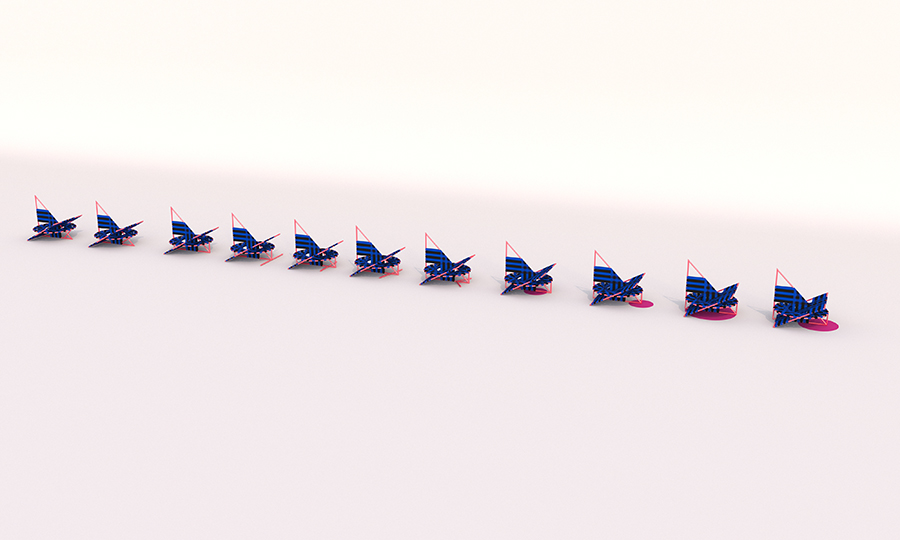

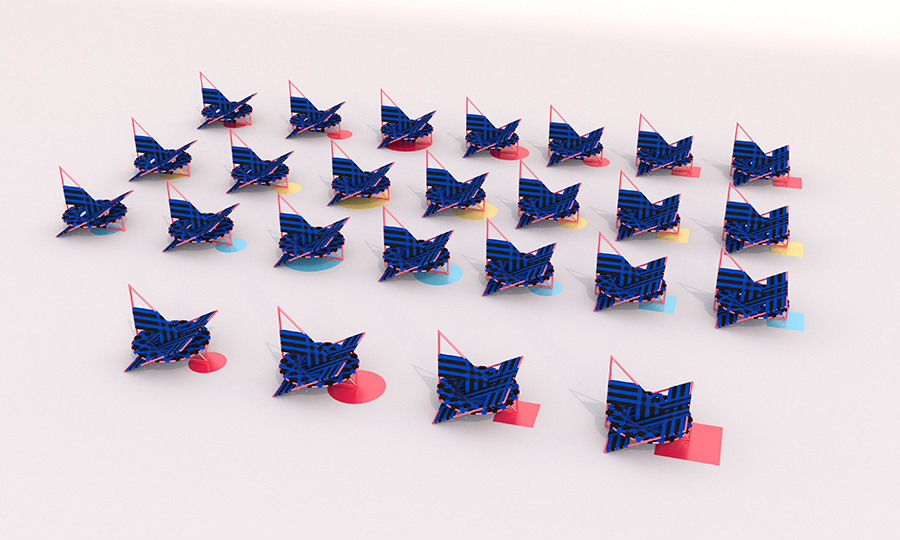

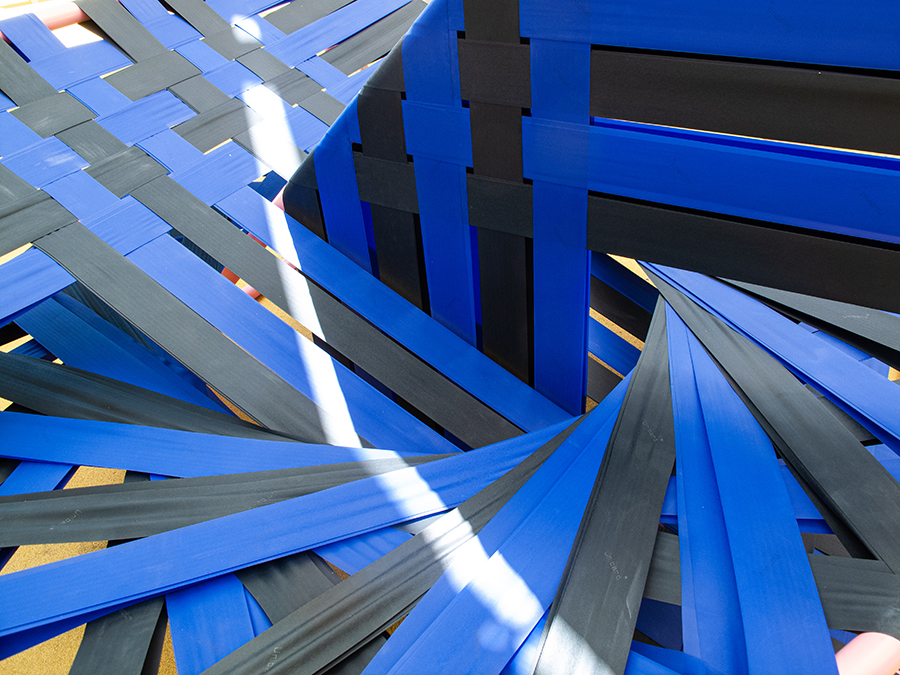

Designed in Stockholm, Sweden, Susie was constructed in collaboration with fine arts fabricator Ellen Sayers in Melbourne, Australia. Like a lot of gym equipment, the form is based on simple geometries: a square, a circle, a triangle, and a rectangle; it is around the size of a double bed, or an oversized sun lounge, or a small sailing dingy—all objects designed to contain or hold a human body. The first iteration of the installation was clad in the resistance bands used in physiotherapy. The colors of the rubber reflected the strength of the bands, black and blue being the strongest bands available. Most gym equipment has a very masculine color palette and the powder pink frame sought to give fitness a more cosmetic cast. In a second iteration, Susie’s cladding was re-woven using a strong textile band: the increase in strength creates a more rigid surface that is better able to absorb and support heavier bodies and more vigorous movements, allowing the installation to do new and different things.

Architects, like other office workers, are notoriously prone to stress injuries related to their work with computers. Going to the gym approaches a form of physiotherapy as much as it is a hobby. When sold as a product, fitness is a promise that we make to ourselves, to keep our bodies functionally and aesthetically “in shape”—to keep them desirable, even. But as urban theorist Maroš Krivý has observed, “fitness” is also a term borrowed from evolutionary biology, which invokes Darwinian ideas about the relation between an organism and their environment. Fitness is about being well-matched to your environment: it is you who adjusts, not your surroundings. Under late capitalism, this means making sure that you can continue working long hours and resist the wear and tear of work—that you don’t break down, that you keep on keeping on. In the face of that scenario, we might ask what other forms of “fitness” could be possible, and whether we can be “fit” for other purposes. As the Swedish artist Fathia Mohidin reminds us, the emancipatory qualities of the strong body have a utility for feminism too. Susie encourages a strength in repose, for bodies of all sizes and ages, whilst considering these questions.

Over-productivity and time poverty is not just an issue for grownups. Children today live highly structured lives—their days are heavily scheduled, perhaps to the same degree as adults these days. To compound this, the spaces of the city where kids spend time outside of the home also tend to be intensively programmed: every inch of our squares, streets and parks tend to be designated for a particular use: here, we shop, here we sit, here we play. Susie challenges this norm; the installation is not a chair, a gym, or a playground, but it has elements of all of these things. It tries not to anticipate what a child or adult might do on or with it, inviting a degree of loitering, testing, and non-productive moments of play.