GENERATORN

ENERGY-PLUS TIMBER HOUSING

FOR STUDENTS AND OLDER ADULTS

WITH SPRIDD AND SEPTEMBRE

LINKÖPING, SWEDEN, 2020-

A NEGOTIATION BETWEEN THE PRESENT AND AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

What does diversity really look like, beneath the surface and in the long term? A design collaboration between Secretary, Spridd, and Septembre, “Generatorn" (Swedish for “The Generator”) is a rental housing scheme for students and older adults (55+) in an emerging neighborhood in Linköping, Sweden. The project is one of Sweden’s first “plus-energy” housing projects in massive timber. Beyond its impressive environmental performance, it represents an experiment in living and designing together, in the midst of a pandemic present.

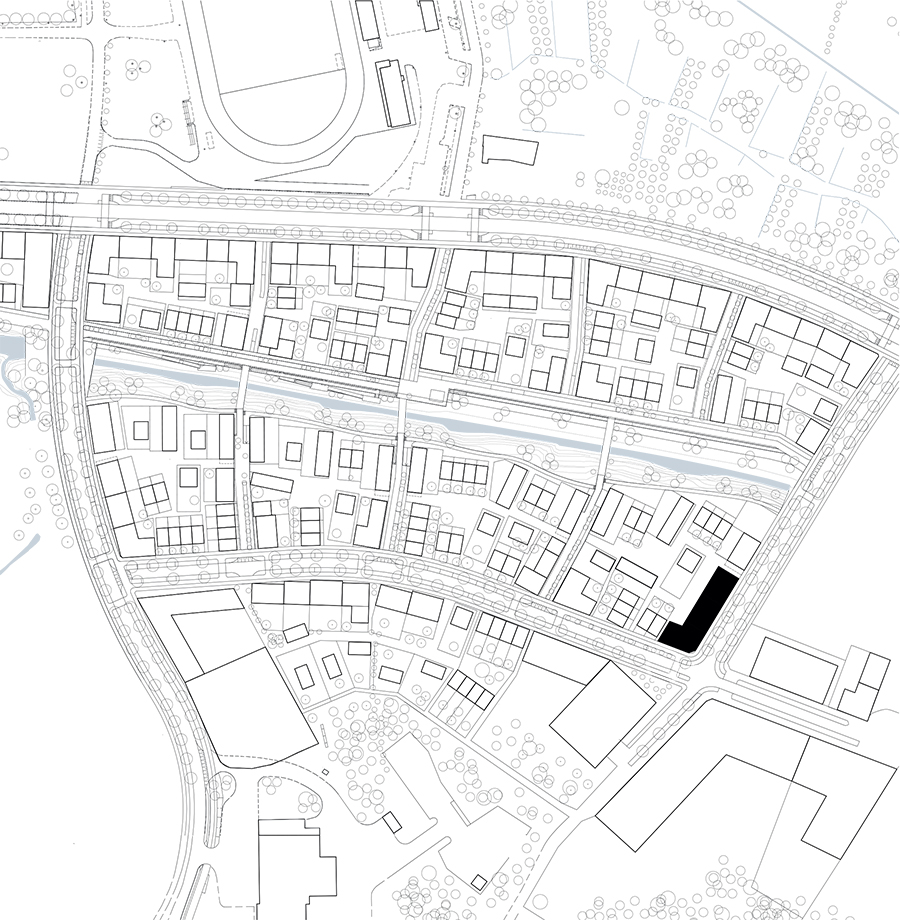

Generatorn was the winning proposal in a land development competition held by the municipality of Linköping, in central Sweden in the fall of 2019, prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. This 112-apartment block is located in the south-eastern corner of Vallastaden, a new housing area close to the main campus of Linköping University, on a site is adjacent to a new Syrian Orthodox Church and a large elementary school. This is a space under intense transformation, as its branded identity as a “flagship” development area necessarily gives way to the messier, more everyday reality of its inhabitation as a residential neighborhood on the periphery of a growing regional city.

Secretary was invited to participate in the project by Stockholm-based office Spridd, in collaboration with Paris-based architects Septembre, with Spridd acting as both project initiator and architect-developer. Designed in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Generatorn is a child of its time—it is the result of hundreds of hours of screen-based video-conference calls, which brought together architects, planners, students, and construction professionals in Stockholm, Paris, and Linköping, many of whom were working from their living rooms and kitchens, where the domestic concerns that define housing as an architectural typology were unavoidably present.

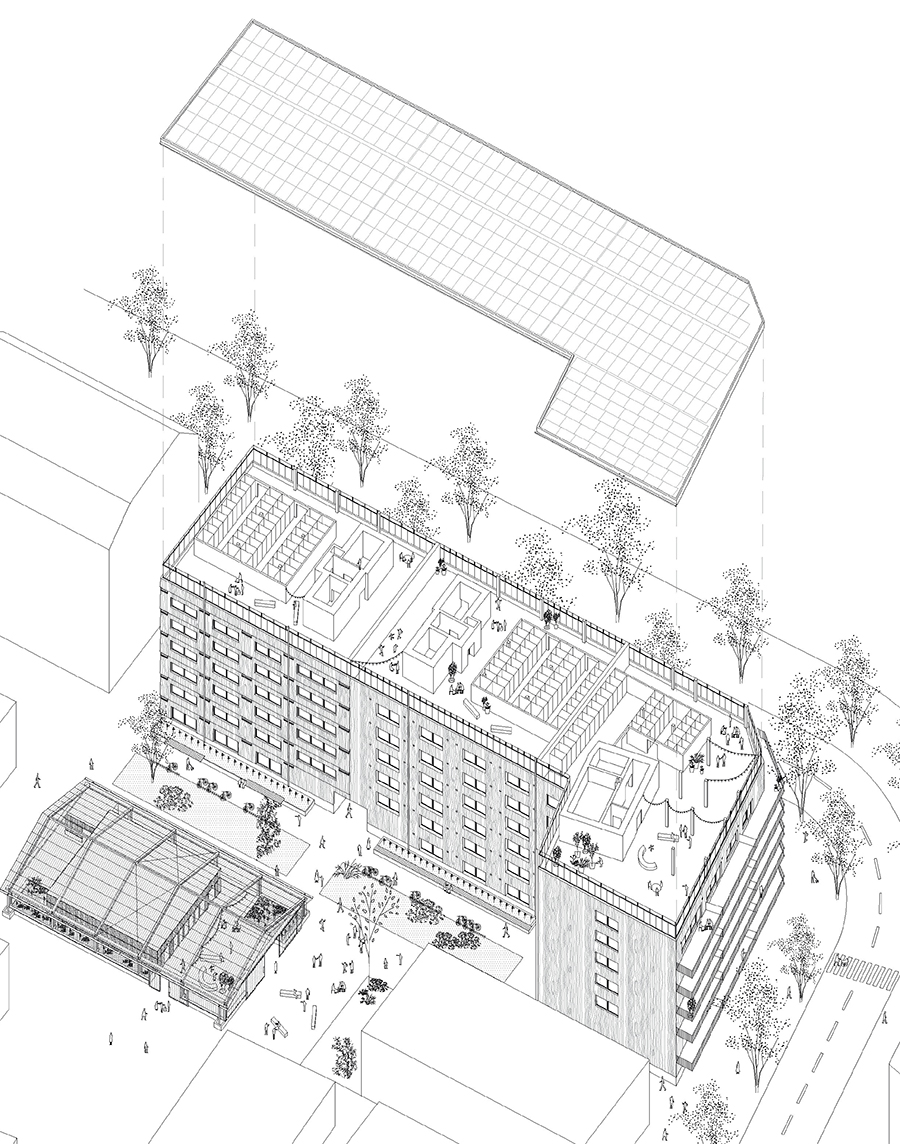

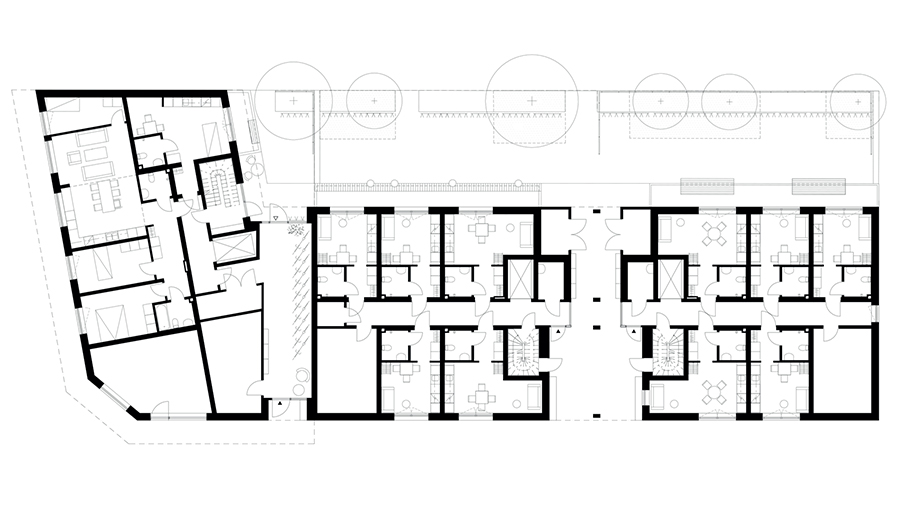

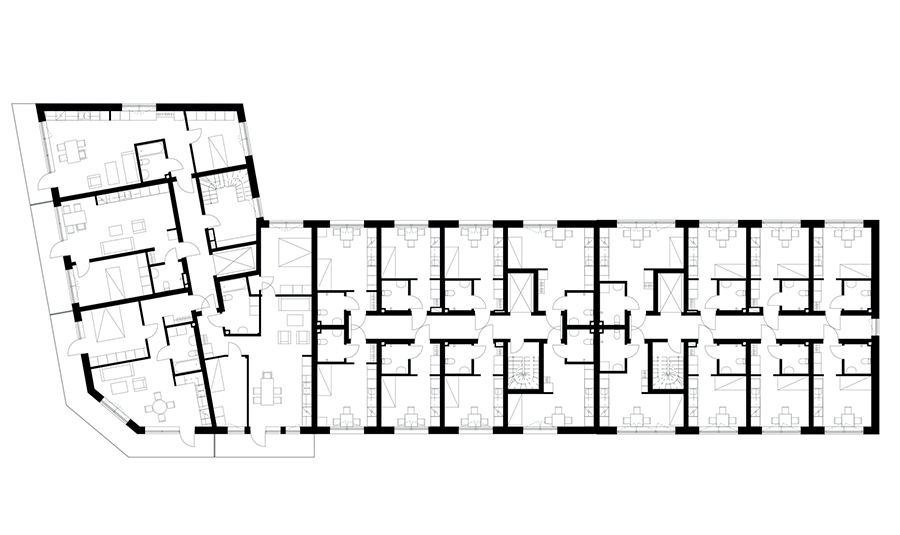

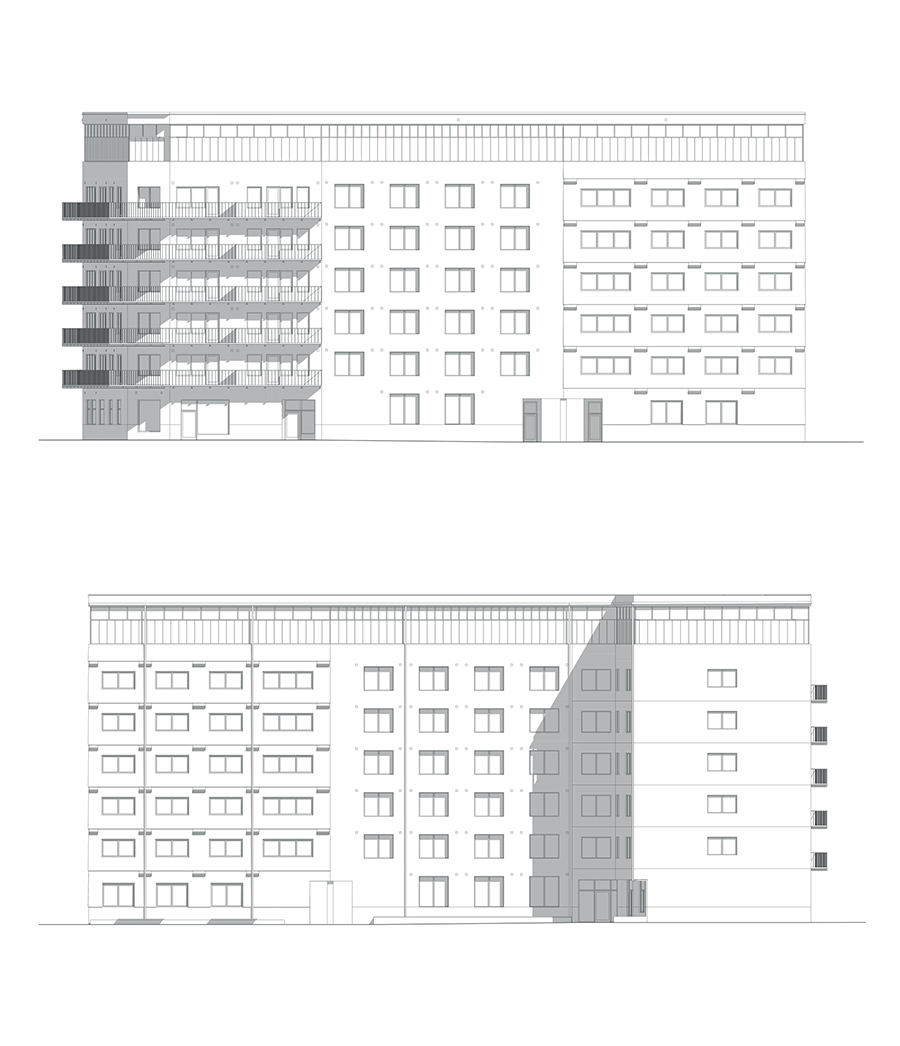

Generatorn’s architecture is a collage of influences: whilst the massing and interior apartment plans were designed collaboratively by all three offices, Secretary, Spridd, and Septembre each offered a unique architectural expression to one section of the tripartite street façade: an elegant lattice of wrap-around balconies designed by Septembre articulates the corner of Lärdomsgatan and Paradisgatan and provides the older-adult apartments in this section of the block with generous outdoor space; the restrained and robust aesthetic of the central façade is the work of Spridd, the most established of the three offices; and the horizontal fenestration and decorative ventilation grilles on the northernmost façade underscore Secretary’s interest in “the cosmetic” as a productively postmodern form of aesthetic variation. As developer-architect, Spridd took the lead on structural design and technical systems, maintaining control over the budget and contact with the building managers who will eventually take over the project. Work on Generatorn thus attempted to shift the individualistic norm of architectural authorship, taking the municipality’s desire for diversity seriously, by pursuing it beyond the surface of the facade and into the project’s design and inhabitation.

This experimental design process was accompanied by a research-driven inquiry into twenty-first student life in Linköping, led by Secretary, wherein student representatives in were interviewed on-screen about their lives and hopes for the future. In these at times moving conversations, students addressed their concerns about climate change, resource shortage, belonging, anxiety, loneliness, self-sufficiency, sociability, access to housing, and quality of life. In many ways, the students’ concerns are echoed the pioneering work of the municipality of Linköping, whose sustainability requirements formed the main armature for the project from the get-go, guiding the choice of structural and technical systems which make Generatorn an energy-plus building.

Generatorn employs a concrete-free, load-bearing structure of cross-laminated, massive timber, which markedly reduces its carbon footprint. Being a “plus-energy” building, further, means that it generates more energy through its roof-mounted high-efficiency solar panels than it uses. To achieve this, the building’s ventilation system operates at the level of the individual apartment, and energy requirements were used to evaluate all design solutions, including the placement and form of windows, the treatment of the winter gardens, and the design of circulation spaces. The sustainable credentials of the project are proven in its Nordic Swan ecolabel certification.

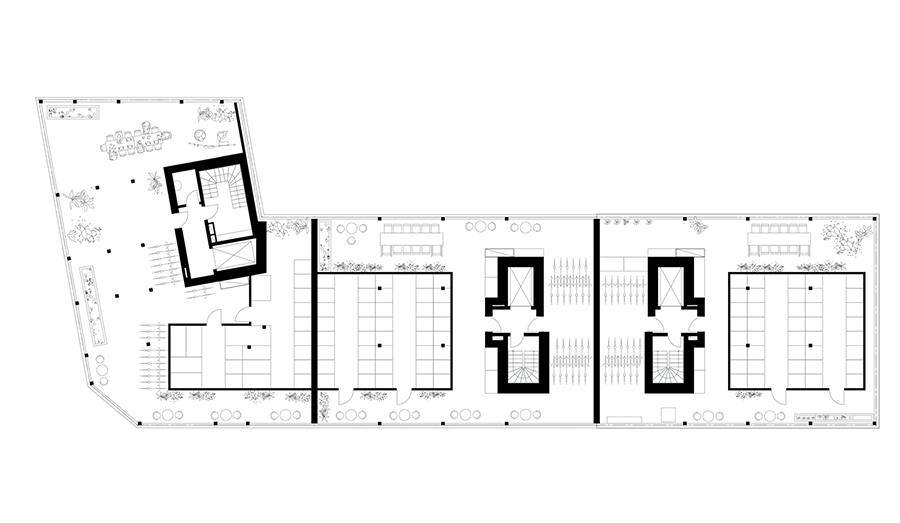

When asked what “quality of life” meant to them, one of the students responded during the dialogue phase of the project, “It’s hard to say for everyone, but if I speak for myself, what is important is: Do I have food? Am I sleeping well? Can I work out? Am I seen, and heard, and loved? Ultimately, it’s those things.” This view underscores the way in which sustainability exceeds technical solutions—it is a condition of inhabitation and a social value that can only emerge in tandem with the lives lived within a building. The primary social ambition of Generatorn is to facilitate intergenerational living, by catering to two very different communities of inhabitants: older adults (55+) and students. Whilst these types of housing have radically different spatial needs, which are recognized in the project by being given their own addresses, both are given access to shared spaces in the form of roof-top winter gardens, a communal greenhouse in the center of the site (“felleshus”), and shared building entries which also provide access through the building to the courtyard. The apartments for older adults have been provided with generous, sun-drenched balconies for gardening and sitting outdoors in the summer months and watch the activity surrounding the Orthodox Church and the school, and the student apartments are designed in a range of configurations, including economical studios and larger apartments with lofts and alcoves. While each student apartment has its own kitchen and laundry facilities, opportunities for communal dining are provided in the winter gardens and the communal greenhouse, which has its own kitchen. An echo of the pandemic can also be felt in these arrangements, which were designed at a time when self-isolation and work-from-home protocols first became mandatory and the need for opportunities to socialize in open-air setting first became apparent.

So, what is diversity, deep down? In the case of “Generatorn,” diversity emerges as a value that can only be achieved in the multiple: it is the product of many architects, with very different design approaches and ideologies, producing a cacophony of at times competing concepts that are distilled down to constitute a single outcome. It is the plural voices and experiences of students from very different backgrounds speaking candidly about the future, in the midst of the design process. It is the possibility of a meeting, when all is said and done and the building stands on its site, between a (hypothetical) recently widowed former librarian, a priest, a high-school student, and a medical student on the corner of Lärdomsgatan and Paradisgatan. It is a plethora of technical solutions that together work to ensure that a single apartment does not consume more energy than it can generate. Generatorn is a building that comprises three street addresses and two programs and one block all at the same time. Diversity, this project teaches us, is perhaps most of all a negotiated state, located somewhere between the constraints of the present and the vagaries of an unknown future.